- A

- A

- A

- ABC

- ABC

- ABC

- А

- А

- А

- А

- А

Who is the Head of the Household?

Svetlana Biryukova, Leading Research Fellow, HSE Institute for Social Policy.

Alla Makarentseva, Head, Laboratory for Study of Demography and Migration, RANEPA Institute of Social Analysis and Forecasting.

Ekaterina Tretyakova, Research Fellow, Laboratory for Study of Demography and Migration, RANEPA Institute of Social Analysis and Forecasting.

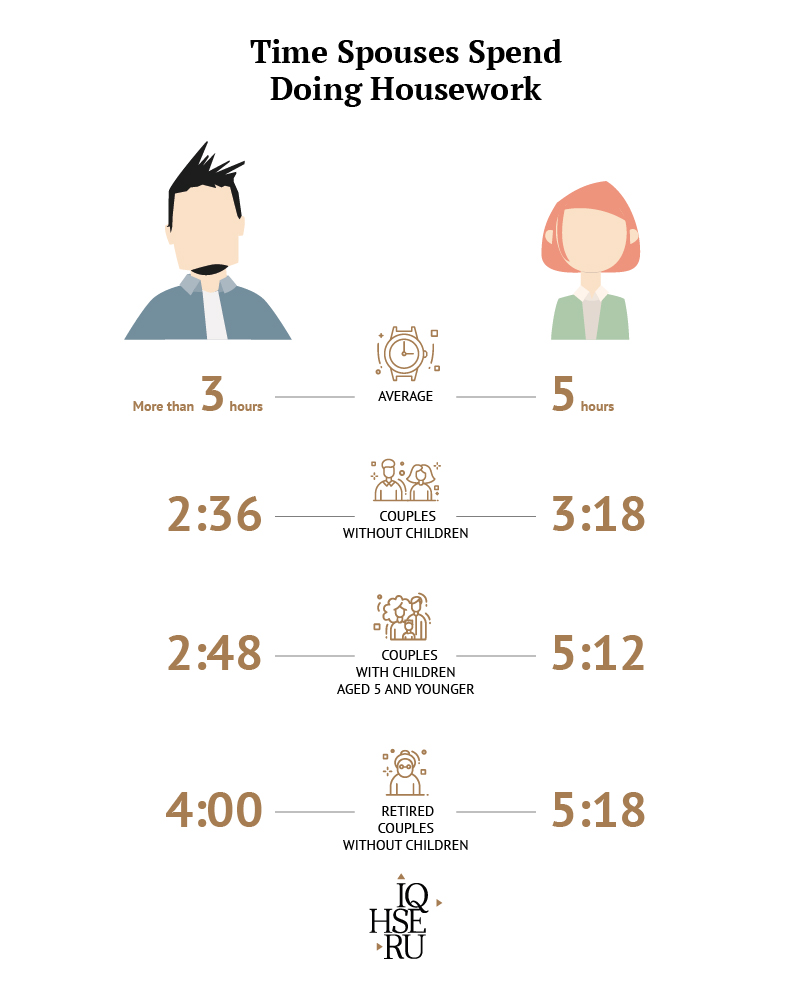

In Russia, self-estimates of time spent doing housework stand at five hours a day for women and slightly more than three hours a day for men.

Men's involvement in household chores is relatively low, but Russian society finds this fair, according to Biryukova, Makarentseva and Tretyakova's study 'Perceptions of Time Spent on Housework among Men and Women'*.

Test for Mutual Understanding

According to the study, how many hours members of a household are likely to spend doing housework depends on a few factors, such as:

- social status . Those of higher status – measured by the level of education, employment and confidence in the future – report spending around three hours each day doing household chores (2.4 hours for men and 3.3 hours for women), while disadvantaged families tend to spend twice as long on it;

- place of residence . Both men and women in big cities have been found to spend about half as much time doing housework as rural dwellers;

- spouses' age and having young children . Couples where both partners are 60 and older and live without young children tend to spend more time than other respondents on housework and give the most accurate estimates of each other's workloads thanks to being together a lot.

Couples with children aged five and younger tend to differ most in assessing each others housework time: while the average wife believes she spends more than five hours a day working around the house, her husband's estimates of her housework time is 1.5 hours longer.

Compared to women, all men tend to overestimate their own and their wife's contribution to housework. One of the reasons, according to the study authors, may be the difference in productivity: having less experience in performing household chores, men might spend more hours doing them and therefore perceive them as more time consuming.

Effect of Stereotypes

Depending on their responses concerning the best time for women to go back to work after maternity leave, the study participants were divided into two groups: conservatives, believing that women should stay home for as long as possible and take care of the family, and proponents of egalitarianism, believing that women should go back to work soon after giving birth to advance their careers and earn money.

Interestingly, 'conservatives' of both genders were found to spend more time on housework than 'egalitarianists'. "In fact, [conservative] men often overestimate the time women spend on household chores – making even higher estimates than the women themselves – thereby supporting the stereotype that women bear a greater responsibility for homemaking than men," the authors comment.

Stereotypes and socal norms appear to have a stronger impact on men, as they rarely think in terms of the cost of domestic work. A proponent of egalitarian views may overestimate his contribution to housework, while a more conservative man might say that his wife "does everything around the house."

What Husbands Resent

Whether or not spouses are happy about the distribution of household duties can give an indication of broader social norms.

On average, 80% of men are completely satisfied with the distribution of domestic chores, regardless of which spouse spends more time at home.

As for women, 44% of those estimating their workload at five hours more than their husband’s are still happy with the distribution of domestic chores, as are 69% of women who feel that both spouses’ workloads are equal.

In Russia, both genders tend to perceive unequal distribution of work around the house as fair and consistent with the woman's traditional role in the family.

Reasons for dissatisfaction with the state of things can differ. For example, some husbands may be unhappy about their wives being able to focus on homemaking only after coming back from work, some others regret having to spent too many hours in the office and not being able to help the wife around the house, and still others resent having to do housework and not being able, e.g. for health reasons, to find a job outside the home.

The researchers conclude that their respondents tend to be unhappy about having to do the type of domestic work which is inconsistent with perceived gender roles, i.e. "men resent having to do 'a woman's work', while women resent having to 'move heavy objects around'." But even though respondents may be dissatisfied with the way household chores are distributed, audio-recorded interviews reveal that this emotion is usually "reflected in the tone of speech" rather than verbalised.

*The study is based on data from the Individual, Family and Society Survey conducted in 2015 by the RANEPA Institute for Social Analysis and Forecasting using telephone interviews (sample size 9,515 people). The quantitative analysis was supplemented by selective listening and review of audio interviews.