- A

- A

- A

- ABC

- ABC

- ABC

- А

- А

- А

- А

- А

Faked to Order

In 1937, an editorial team set up by the Pravdanewspaper produced the Tvorchestvo narodov SSSR [Works of the People of the USSR] poetry anthology, of which more than half were Russian translations of poems written in Armenian, Ukrainian, Kazakh and other languages spoken in different parts of the USSR. Designed to showcase cultural diversity, the anthology was in fact an example of colonial homogenisation. Translators and literary workers had tweaked the originals to suit metropolitan standards and their own ideals of good poetry, according to the Soviet Folklore as Translation Project by Elena Zemskova, Associate Professor of the HSE School of Philology.

.png)

Anniversary of Communist Revolution

The release of Tvorchestvo narodov SSSR was timed to coincide with the celebration of the October Revolution's twentieth anniversary. Maxim Gorky came up with the idea, which was then supported by the Communist Party Central Committee's propaganda department. The Pravdanewspaper set up Dve Piatiletki [Two Five-year Plans], an editorial office responsible for putting together the anthology. The process was led by literary critic Georgi Korabelnikov, while poet Adelina Adalis was in charge of stylistic editing of the translations.

The collection included 255 pieces, mainly poetry. The ratios of languages represented in the book suggest a certain order of preference: 71 texts were in Russian and did not require translation, 37 were translations from the Ukrainian folklore, 13 were translations from Belarusian, 12 from Armenian, 12 from Georgian and 14 from Kazakh (pieces of oral Kazakh folklore praising Stalin were often been published by Soviet newspapers and served as a model for this genre). In addition to the above, there were translations from Tajik, Turkmen and Azerbaijani languages, and a few pieces originally written in languages of ethnic groups living in the Caucasus, Volga Region, Far North and Altai.

‘In addition to the my interest in the translations per se, I found it intriguing that the USSR’s approach was so different from that of most other empires. The latter, according to researchers of post-colonial countries, usually focused on translating books from the language spoken in the metropolis into those spoken in its colonies. The Soviet anthology did the exact opposite by providing Russian translations from the languages of numerous, sometimes very small, ethnicities, to demonstrate cultural diversity’, Zemskova explains. ‘It's another matter that in 1937, the intended outcome had little to do with genuine folkloric variety’.

.png)

How Fakelore Was Born

The Russian State Archives of Literature and Art have preserved many documents illustrating the process of producing the Tvorchestvo narodov SSSR anthology, including original records, interlinear renderings and edited translations, correspondence, minutes from meetings, and workplans of research institutions involved in the project.

Ideally, the process was supposed to run as follows: folklore collectors who spoke the local language would record suitable texts which then would be rendered word for word and line by line into Russian, with indications as to the metre, rhythm, rhyme and other aspects of the original style. Then the interlinear rendering would be sent to poets in Moscow to create publication-worthy pieces in Russian to be added to the anthology. Zemskova found, however, that the actual process did not work as designed, with fakes produced all along the way.

‘Originals made their way to the anthology through a process of adaptation into what the editorial team supervised by the Pravda newspaper senior staff – perhaps the most ideologically savvy people in the country at the time – considered the proper Soviet folklore. Under their guidance, the process worked as follows. Folklore collectors would find a carrier of folk tradition – e.g. a woman who sang mourning songs at funerals – and ask her to improvise a song mourning Lenin's death. Although the style of her improvised song would follow the tradition, it was not genuine folklore as no one in the local culture would ever reproduce the song; therefore such pieces were termed pseudo-folklore or fakelore by researchers', according to Zemskova.

The song would then be rendered word for word into Russian, usually by the same person who first recorded it; the renderer would often try to embellish the text by changing its original structure and imagery.

Then the interlinear rendering would be forwarded to a poet in Moscow for shaping into a poetic Russian translation. In producing artistic translations, most poets focused on meeting the editor's expectations rather than being true to the original and felt free to deviate from the original text and its word-for-word rendering.

‘For many poets, these translations were a well-paid side-job, so keeping the editor happy was far more important for them than accurately reproducing the source text. Therefore, making improvements to the original – and even skipping the original altogether – was considered acceptable. In particular, well-known poets such as Isakovsky, Bedny, Golodny and many others performed this kind of work. Soviet philologist, poet and translator Alexander Romm writes in his memoir that he had a dream of publishing his own poems but kept being rejected by publishers. Instead, they readily accepted his “translations” from other languages – which were, in fact, his original poems. While his dream was to become known as an author in his own right, Romm found it hard to bypass an opportunity to earn good money by publishing his own work as fake translations’, Zemskova notes.

The names of the anthology translators were not published, which helped relieve them of any moral responsibility and saved the editors from potential problems should any of the authors subsequently fall into disgrace.

.png)

All Translations Not Created Equal

Only a limited number of originals and interlinear renderings have been preserved in the archives – a fact suggesting that editors did not used them very often in deciding which Russian translations should go into the anthology. There are two examples, however, which illustrate the editorial process.

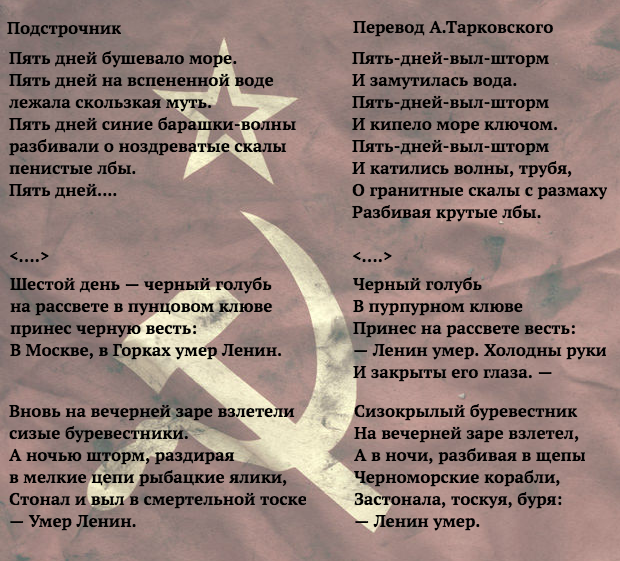

A poem commemorating Lenin's death, which was first published in the Krasny Krym newspaper in 1928 and had allegedly been heard and recorded from an old Crimean Tatar gardener in Bakhchisarai, was selected to be included in the anthology. Its word-for-word rendering was given to Arseniy Tarkovsky who produced an artistic translation by changing the metre and adding new epithets. Tarkovsky's version ended up sounding more high-flown and dramatic compared to the word-for-word piece.

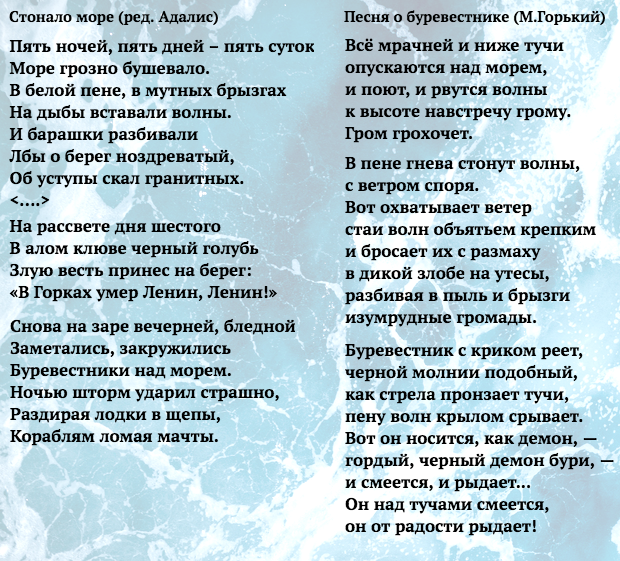

But before the text made it to the anthology, it was further edited by Adelina Adalis; apparently inspired by the image of a sea storm, she gave the poem a strong resemblance to Maxim Gorky's Song of Stormy Petrel.

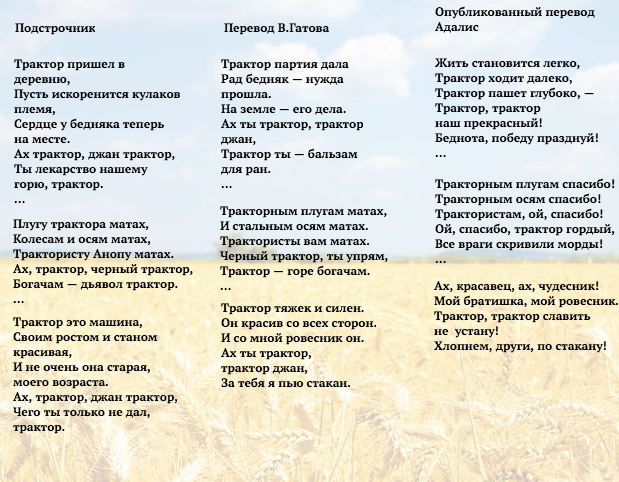

Another example is the adaptation of The Song of a Tractor translation from Armenian. Poet Vasily Gatov's translation was different from the original in that it had 9 instead of 18 stanzas and was written in trochaic tetrameter typical of Russian songs rather than in the original three-syllable accentual verse. To convey the song's oriental flavour, Gatov left a few original words untranslated, such as dzhan (Armenian for 'darling', 'dear') and matah (Armenian for 'prey').

Adalis edited Gatov's translation by emphasising the poem's gleeful mood through repetitions and exclamations while removing the untranslated Armenian words.

Culture of Imitation

Clearly, the exclusively Russian-speaking editors of the anthology were not the primary decision-makers in determining which texts to include in the book. Rather, the selection was made by Pravda’s senior staff who sought advice from the local Communist Party authorities and Writers' Unions in the respective ethnic communities and sent manuscripts for review to Soviet folklore scholars and poetic translators. Some of the reviews were less favourable than others, and some were overtly critical, in particular, of the tendency towards Russification of the original and the use of canonical Russian meters in the translations, as noted, among others, by folklorist Yuri Sokolov. Despite criticism, the editors rarely made changes, being more concerned about the poems' artistic merits than accurate representation of the original. Checking the authenticity of original texts was often reduced to a mere formality.

‘At the start of the project, the editorial team apparently tried to make sure that each original text was authentic: they arranged for field trips to collect and record folklore and ordered word-for-word translations. However, a rigid ideological framework ultimately rendered this work useless. Ultimately, it did not really matter whether or not the original text even existed, and in most cases, the folkloric features were replaced by a set of clichés from the canon of Russian poetry’, concludes Zemskova.

IQ