- A

- A

- A

- ABC

- ABC

- ABC

- А

- А

- А

- А

- А

Sociology of Football

©Essentials/ISTOCK

While the the World Cup was taking place, sociologist Oleg Kildyushov discussed when this sport became the focus of scientific interest, how it has influenced society, and why it is difficult to find the right metaphor to describe the Russian national team's play.

How Sociologists Discovered Football

Sociology is an institutionalized, systematic reflection on modern society which emerged at the turn of the 20th century. Early sociologists could not help but notice the phenomenon of sports, an activity fundamentally distinct from traditional corporal cultural practices. References to sports can be found in classical papers authored by Weber, Simmel and Tönnies although none of them proposed a consistent theory of sports, mainly because the practice of sports was still emerging at the time.

The process of sportization unfolded as a top-down integration of social models: emerging as a body culture of the upper classes, it was later adopted by the middle class and then, after World War I, by the lower strata of workers and farmers. Ironically, despite its destructive nature, the First World War produced an unexpected social effect of democratisation in sports. More details about it can be found in a paper by Christiane Eisenberg.

Soldiers returning from the trenches filled stadium stands and caused a major change in football by giving it an explicitly militaristic form and language. The terms we currently use when speaking about football, such as attack, defence or shooter, have nothing to do with the aristocratic English version of the sport — instead, they were coined by traumatised war veterans exposed to new social practices in France and Germany in the 1920s.

Sociology of Sports was the first book on the topic published in Germany in 1921. Its author was the researcher and writer Heinz Riesse, a pupil of Alfred Weber (a prominent sociologist and brother of the social theorist Max Weber).

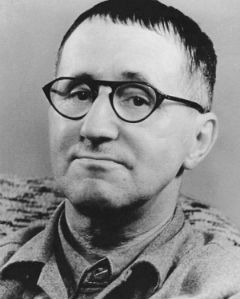

Der Sport am Scheidewege (Sports at a Crossroads), a collection of papers by prominent intellectuals published in Germany in 1928, was an attempt at exploring the new sports reality and its differences from the pre-war sports practiced by students, intellectuals and the upper classes. A few years ago, Logos published an essay from this collection authored by the famous playwright Bertolt Brecht.

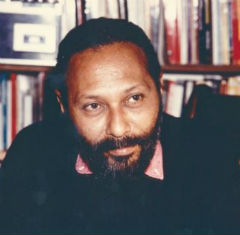

Institutionally, however, the sociology of football began to take shape much later, in the 1960s and 1970s, as academic papers began to be published focusing specifically on this sport and associated social practices. The Birmingham School of Cultural Studies led by Stuart Hall played a key role in these developments.

Unlike scholars of the Frankfurt School, in particular Theodor Adorno, who held negative attitudes towards sports and blamed it for distracting the masses from active resistance to the power of the bourgeoisie, Hall and colleagues examined grassroots cultural practices and proposed an approach to analysing practices such as football which has eventually become the number one sport worldwide.

In France, Pierre Bourdieu led the socio-theoretical reflection on sports and authored a number of related papers in the 1970s and 1980s. Describing social preferences and correlations, he explains, in particular, which social groups tend to choose certain sports practices. Bourdieu and his students’ work reveals that football usually attracts a totally different audience than, for example, martial arts, not to mention polo and tennis.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the West witnessed more research into the cultural and social history of football, with several collections of papers published which reflected a growing interest in the game among scholars in social and human sciences.

The academic institutionalisation of football research was completed in the 2000s, when the Soccer & Society journal was launched. Shortly before the 2006 FIFA World Cup, Germany established Die Deutsche Akademie für Fußball-Kultur (the German Academy of Football Culture) focused on the systematic study of the game as a cultural phenomenon. As we can see, the sociology of football is a fairly recent development, so it is not yet too late for Russian researchers to join the worldwide trend and examine the social and theoretical aspects of this game.

How Sociology Studies Football

The sociology of football relies on three different research perspectives. The first one examines how and why the game emerged in modern society, explores how football has been shaped by its social framework and influenced by the mass media and commercialisation. This approach assumes that football is a social construct evolving over time and seeks to explain its historical dynamics and social functions.

In contrast, the second perspective examines how football has influenced modern society and taken high-profile positions in sports, mass media and other spheres of life. According to Norbert Elias and his followers at the Leicester School of Sociology, the 19th-century England saw what Elias describes as 'sportisation' of traditional folk games as some of them acquired structural completeness and a set of strict rules. In the 20th century, alongside 'sportisation' of physical activity, a parallel process of 'footbalisation' of sports unfolded.

The mass media have helped football become the number one sport virtually worldwide: football is the first thing that comes to mind when people refer to contemporary sports. Both in terms of media coverage and individual perception of cultural reality, football has come to the forefront of public attention, forcing other sports to the periphery.

The third research perspective — described as microsociology — focuses on internal processes in football such as social issues associated with individual clubs, teams, leagues, tournaments, etc.

The three perspectives described above rarely exist in isolation: virtually every paper on the sociology of football mentions them all, although the main focus of study is usually emphasised.

Football as Identity Machine

Political instrumentalisation of football is a popular subtopic in a sports discourse. Even more important from a sociological perspective is that football in and of itself is a political practice, a mechanism for producing group identities. A key question for sociologists is how football generates new solidary groups and new forms of mass identification with an imaginary community. The aforementioned Pierre Bourdieu shared some unconventional reflections on this in his article How Can One Be a Sports Fan?

Recently, I attended the final game of the season between Spartak and Dynamo at Otkritie Arena in Moscow. Being a sociologist as well as a fan, my interest was not limited solely to the game itself but also its context and how its various aspects function in terms of social interactions. It was obvious that the audience consisted of different groups with varying degrees of engagement, intensity of emotions, and group loyalty. For example, some watched the game from the fan sector, some viewed it from the VIP area, and others who held season tickets sat next to the same people at every game of the season.

Although each of these groups were watching the same game, they engaged with it in different ways. For example, people in the fan sector were not passive spectators but an essential constructive element of the game: without its fans, football would be a different genre and a different social institution. A paper by Gunter Piltz offers an interesting perspective on how football fans differentiate themselves from others. When it comes to politics in football, nationalism is the most common form of identity manifested during games played by national teams.

This process has been extensively

discussed in literature.

In Praise of Athletic Beauty,

a book by American culturologist

of German descent

Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht,

reflects on the author's childhood memories

of the so-called 'miracle of Bern'.

In the 1954 World Cup final match held in Bern, Germany unexpectedly won over Hungary's team led by the great Ferenc Puskás. What happened next? Football worked as an identity machine by changing the West Germans' self-perception from a defeated nation to a normal Western country. The change was internal as well as external. According to Gumbrecht, this event marked the end of the post-war period.

Another German sociologist, Gunter Gebauer, described Germany's footbalisation as a process which unfolded simultaneously with the national team's victories in the world championships. Germany has won FIFA's World Cup four times, but from a sociologist's perspective each of these victories was different, according to Gebauer. For example, in 1954, the national euphoria was short-lived as most of the country's population did not practice football, while the upper classes did not identify with the players.

A shift towards mass identification through football was first observed in Germany at the 1974 World Cup. The victory of the legendary German team led by the Bundestrainer Franz Beckenbauer nicknamed ‘Der Kaiser’ coincided with German reunification and completed the country's footbalisation to an extent which no German chancellor has since been able to ignore, as evidenced by Angela Merkel's attendance at all major football tournaments.

The phenomenon of football diplomacy comes to mind in this context. From the perspective of what can be collectively described as 'the West', Russia today is facing political isolation, and there has been a serious debate as to whether a World Cup hosted by Russia is better boycotted and ignored. Football diplomacy, however, provides a window of opportunity by making it advisable for foreign officials, should their national team win, to come over to Russia even if they would have never paid an official visit otherwise: those who fail to attend to their team's success risk alienating their voters who are football fans. Incidentally, politicisation of football can go to extremes. The 20th century saw a real 'football war' between Honduras and El Salvador during a play-off for the 1970 FIFA World Cup hosted by Mexico. Rioting during the matches contributed to existing tensions between the two countries to such an extent that they engaged in a military conflict lasting for nearly a week. What lesson does this striking example teach us? Most notably, it highlights the power of football as an identity mechanism!

In 1950, Brazil hosted the first post-war World Cup. The European spectators who came over to Latin America were exposed to an entirely different way of consuming football and identifying with the national team, characterised in particular by extreme intensity of experience. Visiting Europeans were shocked to see the aftermath of Brazil's loss to Uruguay, its neighbour and historical competitor, when the winning Uruguay launched a nationwide celebration while Brazil mourned the loss profoundly, with fans becoming almost suicidal. For Europeans, such an intense expression of mass sentiment over a sport was hard to imagine. According to French sports historian Fabien Arshambault, football helped Uruguay, a small country sandwiched between Brazil and Argentina, both seeking control over their smaller neighbour, to shape and establish its national identity — just as it had helped the post-war Germans to feel like a normal nation again. For many societies of late modernity, football is more than the number one sport: it is also a unique space for projecting their image of themselves and others.

Game and Social Order

When football first emerged, nothing suggested that it would one day become the number one sport. In fact, this role was originally ascribed to gymnastics when the marriage between sports and politics first occurred. Suffice it to recall Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, ‘father’ of the German gymnastics movement which developed first in the context of opposition to the Napoleonic dominance and fight for Germany's liberation, and later as part of the anti-absolutist action for the country's unification. Both nationalist and liberal trends came together in the history of German gymnastics — a merger of trends which can be considered a formula for modernity. Friedrich Jahn invented a gymnastic oath stating, 'we train new bodies for a new Germany'. It was essentially an attempt at creating a new corporeality for the already free nation. Similar processes unfolded in the Slavic countries; a few Nordic gymnastics systems also emerged. Russian researcher Irina Sirotkina discusses some of these approaches to creating 'national bodies' in her paper on the topic .

.jpg) German sports historian Nikolaus Katzer helps us understand why football ended up taking the dominant position in sports. Explaining the unprecedented growth in football's popularity in the early years of the USSR, he emphasises the open-ended nature of the game and its ability to take a wide variety of forms both in terms of action unfolding in the field and in terms of intensity of the audience experience.

German sports historian Nikolaus Katzer helps us understand why football ended up taking the dominant position in sports. Explaining the unprecedented growth in football's popularity in the early years of the USSR, he emphasises the open-ended nature of the game and its ability to take a wide variety of forms both in terms of action unfolding in the field and in terms of intensity of the audience experience.

As a dramatic composition, a football match can accommodate various types of content: a draw may stir little emotion or cause an outburst, with fans storming each other's sectors, ready to kill. Likewise, a victory with a large score may be taken for granted or celebrated as a national holiday. Despite its well-known rules and a regulated playing space, football takes new and unpredictable forms every time it is played. In the culture of modernity, this game is the last remaining collective performance which is staged in terms of form but spontaneous in terms of content. While any match can be expected to unfold under the referee’s control and to end with a certain score, in terms of intensity of experience, its outcome is always unknown. The sociology of emotions views a football match as a space enabling each spectator to project their own idea of the perfect social interaction such as free collaboration or imposed subordination, especially when national teams play. A stadium then becomes a laboratory for modelling an ideal social order, where each goal scored confirms the effectiveness of a particular social model while each goal missed indicates its shortcomings. From the perspective of political sociology, football is not about 22 people chasing a ball across the field: it is about power, domination and control of territory made possible by a certain way of social organisation. Needless to say, this requires advanced social competencies which many critics of football fail to understand.

Visible Social Geometry

What else can be said about football’s relevance to modernity as well as its political dimension? Most people notice football's 'external policy' aspect, as there are two opposing teams: us versus them. But at least as important is football's 'internal policy' of power relations within a team. Players wearing the same attire often engage in complex interactions and struggle for dominance, higher status and better positions in the internal hierarchy. Every goal scored automatically raises a player’s status within the system. Indeed, in addition to playing against the other team, each player competes with their teammates. Likewise, every fan favours a certain team in general and particular players within the team. Such loyalties become immediately visible during a game and always get noticed by insiders and dedicated fans. From the sociology perspective, football is a visualisation of social geometry; it provides a view of social relations in their pure form.

Violence is another important aspect making football particularly relevant to modernity. Players are allowed to kick the ball but cannot use their hands, yet fouls are often part of the game. The question is how various fouls are dealt with, perceived, and integrated into the game. Every football match is different not only in terms of content, drama and intensity of viewer experience, but also in the extent of violence used.

Norbert Elias referred to football as a condensed expression of modernity, as it allows us, more than any other sport, to observe modernity’s social issues as if through a magnifying glass.

Violence, as well as fouls which are built in the rules, create a grey zone. Those who participate in the game must have a convention as to what constitutes a violation and how permissible it is: if the referee whistled every time the formal rules were broken, a football match would not be a performance worth watching. One should not forget about the spectators, each of whom, as is well known, considers him or herself to be the best player, coach and referee all in one. These three perspectives should more or less overlap for a game to make sense and inform a socially meaningful discussion. According to Umberto Eco, sports debate can be an easy substitute for political debate — or indeed become political debate.

Deficient Habitus of Russian Football

One of the most intriguing questions in the social theory of sports is why national teams play different kinds of football. In trying to answer it, sociology often refers to the academic work of French anthropologist Marcel Mauss who wrote that acquiring certain motor skills is the primary experience of human socialisation: it occurs in a specific social group having its defined ways of bodily existence which Moss called 'bodily skills' and Bourdieu called 'habitus'. The sociology of football focuses in particular on the fact that the manner in which national teams play is shaped by the specific corporeality of their respective ethnic and social groups. Such patterns do not occur naturally; they are social constructs that people develop over time as members of their solidary group.

An experienced football fan does not need voice-over or subtitles to understand which national team is playing: Brazilian, German or Italian. Some national teams focus on one-on-one contact, some others emphasise the technique, while still others play as if they are celebrating Carnival. According to a football expert, the England football team tends to play rugby rather than football. Also possible are various combinations and modifications of these styles.

What can we say about Russian football in this context? It follows from Marcel Mauss' theory that Russian players are supposed to share perceivable football-specific motor skills. But why do they not demonstrate what could be described as a distinct national style? Presumably, the reason is that Russian culture lacks linguistic means for adequate self-description — some social theorists argue that it has not yet completed its modernisation. Perhaps the same applies to Russian football.

It is noteworthy that post-war Soviet football was quite successful: in 1956, the USSR national team won the Olympics in Melbourne, in 1960, it scored a victory in the finals of the first European Cup in Paris, in 1964 and 1972, Soviet football players came second in the European Cups, and in 1966, the Soviet team came fourth in the World Cup. But the 1970s saw a decline, with a long series of defeats, making Dynamo Kiev's victory in the European Cup Winners' Cup seem like an extraordinary event.

The German national team is described as Bundesmaschine and the Brazilian team as Carnival, but no meaningful metaphor exists for the Russian team. According to some observers, this lack of adequate self-description or self-diagnosis stems from the presumed and often criticised lack of social self-organisation skills among Russians. Needless to say, we witness these cultural deficiencies of Russian modernity every day, everywhere, including national football.

Mega Events and Corruption

It sounds trivial that a World Cup is an event of great interest not only for the sports community and fans, but also for bureaucrats and a multitude of other parties. According to former FIFA president Sepp Blatter, every bidding process for hosting football championships comes with intense bureaucratic and corruption-related clashes, as competing countries' elites seek to demonstrate their infrastructural and technological superiority, advanced managerial competencies, etc.

In addition to image gains, hosting countries can anticipate tremendous economic benefits, since most infrastructure projects for the World Cup would have never been undertaken otherwise. One might argue that by making an international commitment to host a football mega event, national elites compel their country to modernise. In addition to sports facilities, this usually leads to the creation of new transport, logistics, and other types of infrastructure. If it had not been for the World Cup, Russia would have never constructed stadiums in 11 cities within a relatively short period. Upgraded transport infrastructure and and an improved hospitality industry in host regions provide a strong impulse for further development. However, the WorldCup, like any other mega event, is inevitably associated with corruption.

Why is social theory drawn to mega events? Because they reveal, in a concentrated form, the different and sometimes conflicting interests — economic, corruption-related, environmental, identity-focused, etc. — of major social groups and communities, local as well as global. At the same time, a sports mega event can disclose much more about the host than this country would like. The world media spotlight allows outsiders to learn about the local systems of power and property. Each country's process of hosting the championship is unique: the way Germany prepared for the 2006 World Cup was different from Brazil's preparation for the 2014 World Cup, and if China had got to host the 2026 World Cup it would have been a completely different picture. Russia's process, however, was unique in terms of corruption scandals, such as the infamous case of St Petersburg's World Cup stadium project.

Different approaches have been used for hosting and managing sports mega events. In Russia, a dedicated vice-premier position is created for every hosted event, reflecting the specific nature of the country's managerial culture and the political elites’ awareness that this task is impossible to perform by doing business as usual. At the time of the Sochi Olympics, there were indications that Russia was gradually recreating a system similar to the Soviet Sports Ministry (Gossport). Once it became clear that Moscow would host the 1980 Olympics, a vice premier position was introduced in the USSR to govern the preparation process; now we are witnessing a revival of this Soviet approach to management in today's Russia.

Last Pocket of Free Play

After the doping scandal that tarnished the International Olympic Committee's reputation with millions of people, the World Cup may be the last high-level sports event still offering some hope (or perhaps an illusion) of no direct political interference in the game. We do not know, as I’m writing this, who will win the World Cup in Luzhniki on July 15th. Yet we are certain that no one will be excluded from the competition under a false pretext and that players or fans of any team will not be banned from displaying their national flag. In this sense, a football championship may be the world's last remaining game which is still spontaneous and unpredictable — the essential characteristics of modernity. Very soon, our stadiums will feature an event which is not only about contestation and power but also about freedom and creativity. It is to be hoped that this last chance for a global free game will not be missed and will bring pure joy to the world, despite the dubious socio-political context.

IQ

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)