- A

- A

- A

- ABC

- ABC

- ABC

- А

- А

- А

- А

- А

Abusive Supervisors

©ISTOCK

Abusive supervisors who undermine and bully employees cost U.S. corporations an estimated $24 billion annually. Evgenia Balabanova, Maria Borovik and Veronika Deminskaya are the first researchers to study the problem in Russia.

What Is Abusive Supervision?

Abusive supervision should not be confused with merely an authoritarian management style — or with any other management style. By undermining their subordinates through insults, rudeness, sabotage, petty tyranny etc.), abusive supervisors pursue personal rather than corporate interests.

Researchers in the U.S. and Western Europe have been examining the situation of abusive supervision over the last 20 years. In Russia, however, this is the first study focusing on this phenomenon and is based on findings from an anonymous survey of students taking an online course at the Open Education Platform (198 questionnaires) and from more than 20 case descriptions of abusive supervision shared by some of these students.

Abuser in Action

Based on the survey results, the least common abusive practices in Russian companies include nationalist and sexist attacks (indecent remarks, comments and gestures).

The most common abusive behaviours mentioned by the respondents include:

forcing employees to perform routine and unskilled work (reported by 24% of respondents);

imposing changes which affect an employee without prior discussion with him or her (23%);

public chastisement of an employee in front of co-workers (22%);

deception (19%);

disregard for employee opinions and initiative (19%).

In total, the study authors list 21 indicators of abusive supervision, including, in addition to the above, behaviours such as breaking promises, ignoring achievements, intentionally interfering with an employee's work, undermining his or her career, unfairly distributing remuneration, being rude, wrongfully accusing employees of incompetence, subjecting them to ridicule, etc.

Seeking Personal Power

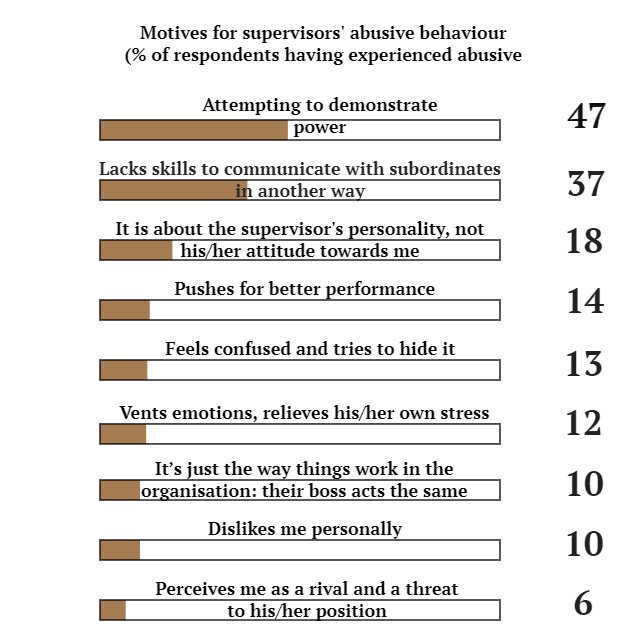

Of all respondents, 56% have encountered some form of abusive supervision, which they often explain by the supervisor's desire to demonstrate power and a lack of the skills needed to communicate with subordinates properly.

According to the researchers, this response confirms that abusive supervision is a 'social rather than psychological' phenomenon and cannot be explained by one's personality but instead reflects 'power relations within the organisation’.

Source: calculations by the study authors.

Personality, however, is always a prerequisite of abusive behaviour. Foreign authors associate its prevalence with specific socio-demographic characteristics such as age (younger supervisors are more likely to be rude towards subordinates) and gender (men are more inclined to use a harsh management style, while women tend to rule with a softer hand).

But the study from Russia does not confirm these findings: the largest part of respondents with experience of abusive supervision were women whose supervisors also were women. In addition to this, older supervisors were reported to be more likely to humiliate and undermine subordinates.

Carrots and Sticks

According to foreign researchers, certain organisational environments — such as an unfriendly overall climate, a rigid hierarchy or a weak remuneration and promotion system — can lead to supervisors' unethical behaviour.

The Russian researchers associate the following factors with abusive supervision:

intensity of communication between supervisors and subordinates. The more time employees spend in direct contact with the boss, the more negative messages they receive;

lack of positive management practices. Employees who have not experienced positive developments in the workplace in the past two years (e.g. enriched content of work , career advancement, etc.) are more likely to report abuse;

employee remuneration dependent on personal relations with the boss. A system in which the amount and criteria for remuneration are left to the supervisor's discretion easily becomes a breeding ground for abusive supervision as those who control the vital resource can be tempted to abuse their power. The authors emphasise this finding as 'particularly significant, given that most supervisors today continue to rely on the carrot and stick policy'.

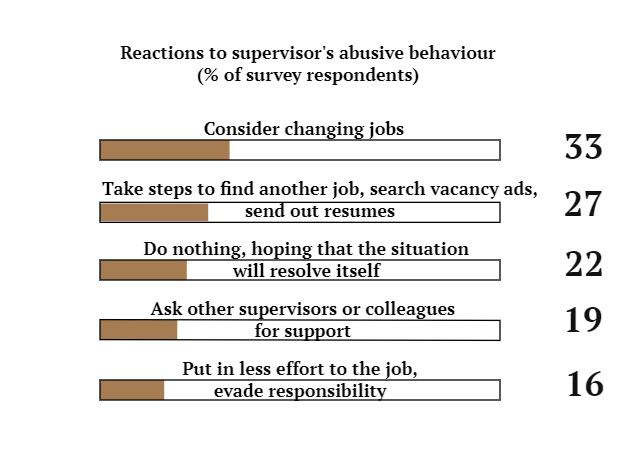

Response from Abused

The most common response to abusive treatment is to consider changing jobs or taking concrete steps to find new employment. One in five abused employees adopt a wait-and-see attitude in hopes of the situation improving without their input. Very few, if any, choose direct confrontation with the abuser, such as arguing or defending themselves; at best, most would seek support from third parties.

Source: calculations by the study authors.

'The best ones leave, the worst ones stay and tolerate it,' the researchers sum up. 'High-performing employees who are confident, qualified and in-demand are more likely to report the problem, defend themselves or leave. In contrast, low performers prefer to keep quiet or go into hidden opposition such as sabotage, damaging or stealing company property and applying minimal effort to their work'.

Examine and Revise

Abusive supervision has a negative impact not only on employees by undermining their physical and psychological wellbeing, causing burnout and lowering life satisfaction — but also on the company's bottom line.

Financial loss of U.S. companies due to the consequences of abusive supervision such as absenteeism , healthcare costs, lower productivity and loss of employees, are estimated at $24 billion annually. No such estimates have been made for Russia but the negative impact is obvious, since companies are unable to use their human resources effectively and thus rob themselves of the potential gains that humane supervision could bring.

Abusive supervisors cause significant damage to companies. According to the researchers, this is a good reason not only to address the phenomenon per se but also to revisit traditional views on the value of 'strong' management in the context of appointment to supervisory positions, determining the scope of supervisory authority and assessing supervisory performance.

IQ