- A

- A

- A

- ABC

- ABC

- ABC

- А

- А

- А

- А

- А

Climate Control

THE JIM JEFFERIES SHOW, 2017–2019

A two degree Centigrade increase in global average temperature will lead to catastrophic consequences for the planet. Humanity has a maximum of 20 to 30 years to prevent this. Having studied the impact of warming on countries in Central and Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia, Georgy Safonov, Director of the HSE Centre for Environmental and Natural Resource Economics, warns that responding to climate change does not seem to be a top priority for the region's governments, while potential threats are assessed only in economic terms and almost never as a social challenge.

What's Wrong with the Weather?

Rapid Warming

The study focuses on 27 CEECCA (Central and Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia) countries: Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Tajikistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

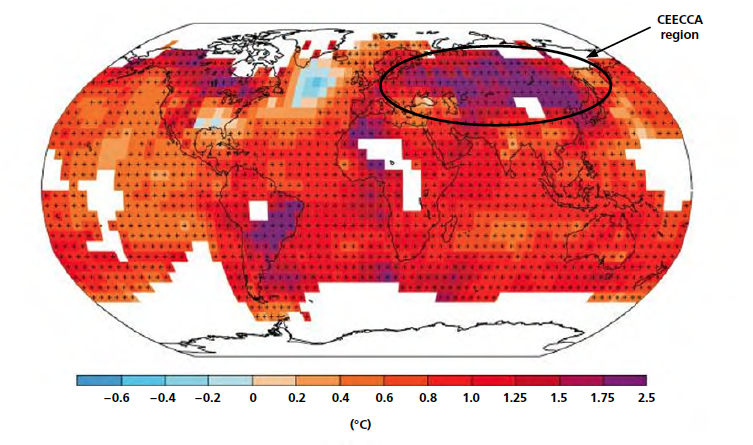

The observed pace of warming in the region is reported to be higher than the global average. According to IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) data, while the average global warming has been around 0.8°C in the last 160 years, an increase of 1°C –2.5°C has been observed in the last 112 years in CEECCA countries, with the fastest pace of warming reported in the last two decades.

Observed change in annual mean surface temperature, 1900–2012.

Deep red and deep blue in the CEECCA region indicate warming by 1.0°C to 2.5°C in the last 112 years.

Source: IPCC AR5, 2014

Change in Precipitation

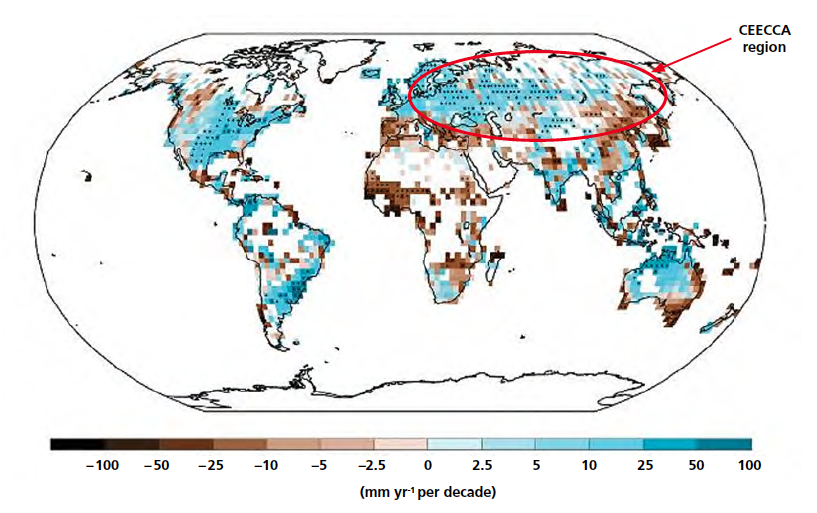

As far as precipitation is concerned, the studied countries faced major deviations from the norm between 1950 and 2012, with annual decreases of 2.5 to 50 mm per year per decade in some areas of Southern Europe, Caucasus, Central Asia and Russia and increases of 2.5 to 100 mm per year per decade in northern areas of the region. Overall, CEECCA experienced far less precipitation decrease than many of its neighbouring areas such as Southwestern Europe, the Middle East, China and Africa.

Observed change in annual mean precipitation, 1950–2012

Blue indicates increased precipitation, brown shows a decrease and white means no change in precipitation since 1950.

Source: IPCC AR5, 2014.

Worrying Scenarios

According to Safonov, 'The climatic changes observed are already affecting all countries, but the worst is yet to come. IPCC projections of future climate change are worrying: all scenarios show that warming will continue and further increase by the end of the 21st century.'

Higher concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere cause warming of the Earth's surface and greater thermal radiation. According to the most optimistic RCP2.6 scenario, CO2 concentrations are expected to reach their peak between 2010–2020 and then begin to decrease, so that the average annual temperatures in CEECCA countries may change by 1°-3°C before 2100.

The most pessimistic scenario RCP8.5 projects a consistent increase in CO2 concentrations throughout the 21st century, with temperatures in CEECCA countries rising at least by 5°–7°C before 2100.

In terms of precipitation, the optimistic RCP2.6 scenario projects a slight increase of up to 10%, while the pessimistic RCP8.5 warns that the CEECCA region may face decreases in precipitation of up to 30% in its southern parts and increases of up to 40% in other areas by the end of the 21st century.

This means that southern countries and regions will experience more frequent and dangerous droughts and heat waves, while their northern and eastern neighbours will be increasingly affected by floods, extreme rains and other hydrometeorological hazards.

Besides damaging the ecosystems and undermining the countries' economies, these changes will have diverse and dire social implications, mainly due to their impact on human health and wellbeing, life expectancy and quality of life, which are likely to deepen existing inequalities and cause unprecedented migration.

Natural Disasters: What to Expect

A two-degree C surface warming is likely to lead to the migration of some 300 million people, while at 3°C, it could leave three billion people without access to drinking water and thus provoke their relocation.

While safe drinking water is available, on average, to 84% of people in CEECCA countries, the situation in some areas is more worrying, with just 47% of the population in Tajikistan, 51% in Uzbekistan, 61% in Armenia and 66% in Kyrgyzstan having access to potable water.

Floods, shortage of safe drinking water and pollution of bodies of water could increase infection hazards. Drought-induced dust storms are capable of transporting hazardous pollutants over long distances. Rising temperatures will cause more frequent and longer heatwaves affecting people's health and leading to higher morbidity and mortality.

The 2003 heatwave in Western Europe killed 74,000 people, while the heat and air pollution caused by forest fires in the Central European part of Russia in summer 2010 claimed 54,000 lives.

Food security is also at risk. Climate change over the next 20 to 30 years will reduce the yield of cereals and other crops. Following a climate-induced rise, agricultural production has already begun to decline and is likely to suffer enormous damage in the future unless adequate climate-change adaptation measures are taken.

In Russia, severe droughts in 2010 and 2012 dramatically decreased overall crop yields by 33% and 25% respectively. Without adaptation to climate change, the annual economic loss caused by reduced crop yields in Russia could reach as much as 4 billion U.S dollars.

Melting permafrost threatens three quarters of the Arctic population and is causing damage to infrastructure such as buildings, gas pipelines, heat supply systems, etc. This is particularly important for Russia where permafrost covers two thirds of the territory.

Damage from permafrost melting has already caused more than 5,000 accidents at oil and gas pipelines and has affected roads, buildings, and power lines.

In addition to this, dangerous viruses and bacteria previously buried in frozen ground can be released and leak into rivers and other bodies of water increasing the risk of deadly infections spreading.

In Yakutia alone, there are now more than 15,000 burial sites of cattle killed by anthrax over the past few decades.

Anthrax spores can survive for more than a hundred years, and warming can cause them to be transported over long distances and potentially affect both nearby and remote regions.

Threats under Control

National reports published by CEECCA governments reveal the current level of climate change risk awareness.

Having analysed country reports under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Safonov found significant differences across the CEECCAA countries as well as a few common trends:

all countries consider rising surface air temperatures to be a major risk factor;

two-thirds of the states, in particular Armenia, Georgia and Hungary, are concerned about the impacts on health and expect them to increase and to be serious;

about half of the countries, in particular Armenia and Kyrgyzstan, are worried about the potential spread of infections;

most countries, in particular Armenia, Azerbaijan and Serbia, expect negative consequences from flooding;

one-third of the countries foresee disastrous droughts;

Albania, Slovenia and Russia are concerned about coastal erosion and rising sea levels;

mountainous countries of the Caucasus and Central Asia (Armenia, Georgia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan) are aware of the risks of landslides, rockfalls and avalanches.

reduced access to water is expected in Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan), Moldova and Macedonia;

Latvia and Russia are particularly concerned about climate change impacts on urban and rural infrastructure and about damage to forests;

half of the states anticipate threats to food security (food production).

Изменение климата: приоритеты правительств стран СЕЕССА

Source: author, based on country reports to the UNFCCC

Half-hearted Response

But acknowledging that a problem exists does not equal solving the problem. According to the study’s findings, many states have yet to make substantial progress in designing relevant national strategies, while their government’s declarations are not always supported by real actions.

This is due, among other things, to a lack of finance, the relatively low priority of climate issues compared to traditionally perceived development needs, and poor awareness of impending climate-related challenges.

Some countries tend to emphasise the potential short-term benefits of climate change and to ignore its long-term consequences: one-third of CEECCA countries, including Belarus, Bulgaria, Estonia, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Russia and some others, believe that climate change can have a positive effect on the agricultural industry.

While higher-income countries, such as Russia and the Baltic states, are showing more progress in their climate policy, low- and medium-income economies such as Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, due to poor capacity for data analysis and R&D and lack of relevant skills, require international support.

Russia's Reactive Policy

Russia adopted its Climate Doctrine in 2009 and the Government's Action Plan for its implementation in 2011. But, according to Safonov, the country still does not have a coordinated policy on climate change adaptation. The researcher describes current measures as 'reactive' rather than 'preventive' in many vulnerable areas such as compensating crop losses and the impact of flooding, fighting forest wildfires and responding to heatwave emergencies.

In this context, in September 2019, Russia ratified the Paris Agreement, an international treaty that requires its signatoriesto keep the increase in global average temperature to 'well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels' and to achieve, as soon as possible and no later than the second half of this century, a balance between anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases and their removal by ecosystems.

In December 2019, the Russian government adopted a national plan for adaptation to climate change which requires industries and regions to design their own sectoral and regional adaptation strategies and provides for specific measures to be implemented between 2020 and 2022. While this decision is important for the country, according to Safonov, the plan has a number of drawbacks:

no funds have been allocated for its implementation;

the timelines for developing sectoral strategies have been extended by 1.5–2 years;

the Russian regions are 'recommended', rather than required, to draft their adaptation programmes, which can be perceived as optional and ignored by officials.

'Unfortunately, as revealed by the implementation of the 2014 Climate Doctrine action plan, the effect of recommendations is limited unless supported by a focused and rigorous federal policy', Safonov notes. He warns that delays are unacceptable in the current situation and joint action involving all players – including industry, businesses and civil society – is urgently needed.

IQ